»The Faroes are a mini laboratory.«

Lars Fodgaard Møller's words come crackling down the phone line from the Faroese capital, Tórshavn. He is the chief medical officer of the Faroe Islands, and the past few weeks have been the most hectic experience he can ever recall having.

The North Atlantic archipelago is badly affected by the coronavirus outbreak. With 92 cases out of a population of some 51,000, the proportion of reported cases of contagion is far higher than in the rest of the Kingdom of Denmark which the islands are part of. But both this figure and the hectic atmosphere are also due to the fact that the Faroes are testing far more intensively than most other countries.

Authorities in the tiny cluster of islands are still following a strategy which Denmark and many other countries have given up, tracing every single case of Covid-19 and painstakingly mapping the chains of contagion across the 18 islands. Any patient with even mild symptoms, who in the rest of Denmark is merely told to stay at home, is immediately tested.

This is potentially an observation of immense importance. It would be material for a scientific paper.ALLAN RANDRUP THOMSEN, PROFESSOR AT THE UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN

For this reason, the archipelago is among the places in the world that, proportionately, have the highest level of testing — higher than even in South Korea which has pursued a strict policy of containment.

This has given local health authorities a unique vantage point across the global sea of contagion.

»If we had a board that was big enough, we would be able to connect almost all the cases of contagion,« Lars Fodgaard Møller says.

As this unique detective work has unfolded across hectic days, the chief medical officer found himself increasingly puzzled. If you map the contagion in the North Atlantic, it immediately becomes clear that some patients set off long, aggressive chains of contagion. But others do not.

Kisses, but no contagion

Lars Fodgaard Møller first shared his observations at a press briefing in Tórshavn last Thursday. There appeared to be two different types of coronavirus at play, he stated: one spreading so little that it stood out in the contagion mapping, and another spreading so easily that »people just passed each other and got it,« as he put it at the press conference.

To Berlingske he further explains his observations on how the virus has spread in the Faroes:

»We saw that the first cases we had were not contagious. We could see that although they had had kissing contact, they hadn't passed it on.«

»Then a different type came from Denmark and from Iceland which spread really quickly, so these two chains of contagion became completely central,« Lars Fodgaard Møller says.

It's taking up a lot of resources, but I do think we need to continue with this strategy.LARS FODGAARD MØLLER, CHIEF MEDICAL OFFICER OF FAROE ISLANDS

Could this not simply be due to some carriers of the virus spreading it more easily than others?

»But this continues in the next generation as well, so contacts and contacts of contacts. It appears to apply all along the chain. But we can't say anything definite until we have some genetics done,« Lars Fodgaard Møller says.

The chief medical officer stresses that he is not claiming to have any scientifically proven conclusions, merely immediate observations from the field amid the global wave of contagion.

But the Faroese observations were strong enough for him to contact Statens Serum Institut, an institute under the Danish Ministry of Health whose main duty is to ensure preparedness against infectious diseases.

And medical scientists here recognised the North Atlantic hypothesis.

Flushing perfectly with the hypothesis

Anders Fomsgaard heads the virus lab at Statens Serum Institut and is one of Denmark's leading authorities in this field. He has been closely following the global experiences so far.

And he says that several studies now support the hypothesis that there are two main strains of coronavirus, as indicated in a Chinese study at the beginning of March: a so-called S type, which is considered to be the original one, and a more recent L type.

This is also the hypothesis which Statens Serum Insitute is now working from.

»The Chinese study was the first to indicate this. There are two strains circulating: an L type which spreads a bit more easily that the original S type. The L type is more widespread now, and we have so far only seen this strain in Denmark. But we are gene testing far more samples now,« Anders Fomsgaard at Statens Serum Institut states in a written response to Berlingske.

It is not yet known whether the mortality rates for the two strains are also different.

Off-hand, the observations from the Faroe Islands appear to flush perfectly with this hypothesis. But Anders Fomsgaard is eager to stress that he is not making any conclusions on the basis of the Faroese observations.

»I don't know this particular survey. It may not necessarily be down to different viral strains but is worth investigating,« he writes.

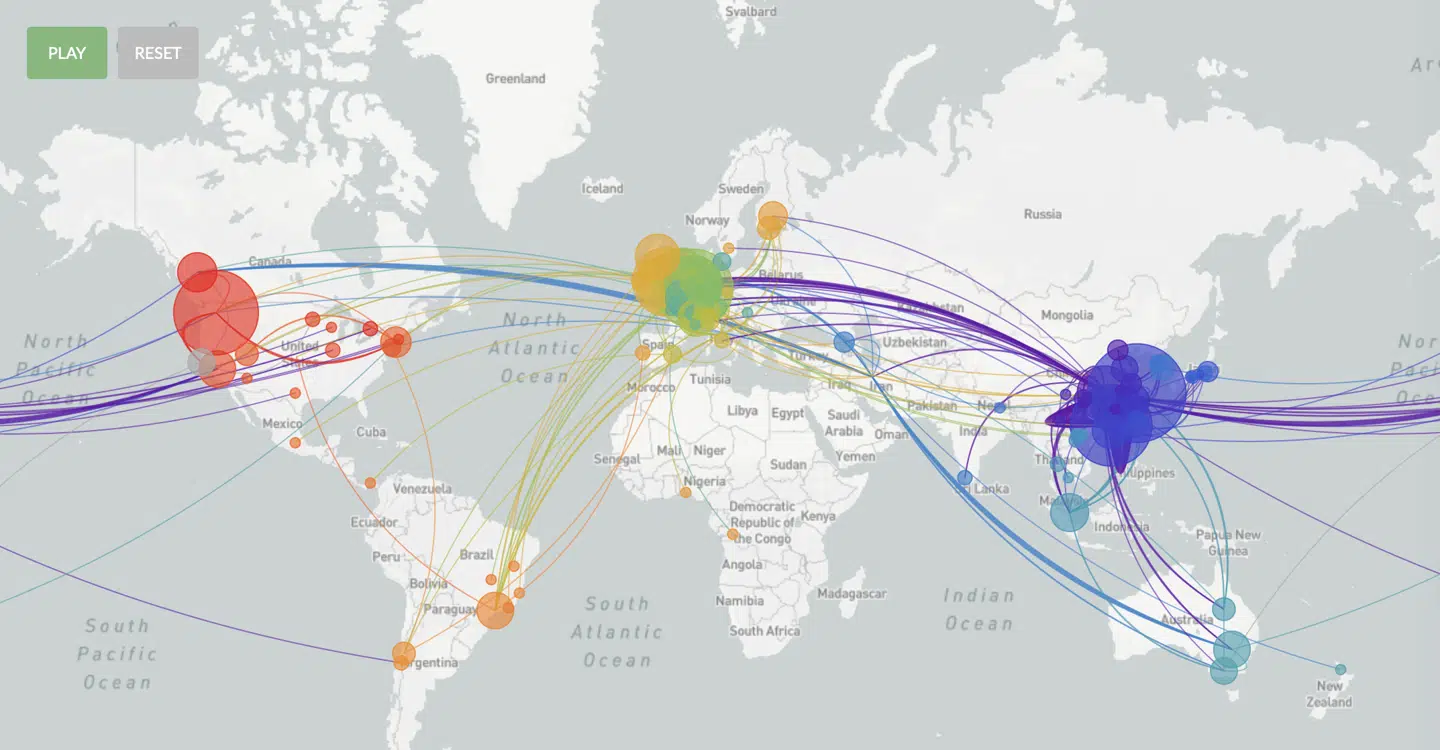

And this is exactly what scientists across the world are now busy doing. They are mapping mutations of the virus, however large or small, in cases of Covid-19 that have been recorded in different countries. Some of this work is carried out through the research network Nextstrain.

So far, ten Danish samples have been gene-mapped in Danish laboratories. All were of the L type. But in the coming days some 100 more samples will be tested, according to Anders Fomsgaard.

Scientifically interesting but not yet proven

As such, research into the hypothesis of different strains is scattered, and several Danish scientists are calling for more systematic studies to be done before drawing any definite conclusions on the presence of different viral strains.

Niels Høiby, a professor of clinical microbiology at Denmark's leading specialist hospital Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, says it is news to him that Statens Serum Institut is now operating with the hypothesis of two viral strains.

»This is scientifically interesting,« says Niels Høiby, who is also a member of the epidemic commission for the Copenhagen Capital region.

But he stresses that what is most important in terms of fighting the contagion is whether one type of the virus does appear to spread more easily than the other, and this remains, for now, a hypothesis.

Allan Randrup Thomsen, a virologist and professor at the University of Copenhagen, sees promising potential in the Faroese data, precisely because of the detailed mapping of reported cases.

»This is potentially an observation of immense importance. It would be material for a scientific paper. So I really do hope that they are getting samples sent off to Statens Serum Institut for gene sequencing,« he says.

Tom Gilbert, a professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Copenhagen, points out that the known differences between the two viral strains are so small that it is questionable whether to even consider them biologically different.

»It's important to clarify whether there are biological differences between the S and the L types and whether they affect the body differently. If they are biologically different, they may require different vaccines,« Tom Gilbert says.

But if the hypothesis of a more contagious variation is confirmed, it may also be an early indicator that the coronavirus follows a well-known — and reassuring — pattern from flu epidemics.

»Very often, when a virus changes, it changes into being more contagious but less disease causing. And that would be amazing, because then we are looking at, roughly speaking, it being more like the flu. Then we might actually start to see the light at the end of the tunnel,« Allan Randrup Thomsen says.

The chief medical officer of the Faroe Islands, Lars Fodgaard Møller, confirms that he has already sent samples to Statens Serum Institut.

Meanwhile, he and his colleagues are continuing their detective work to map a contagion that may prove especially risky for the Faroe Islands due to the limited resources of the local healthcare system.

»This is the only option we have for containing it. It's taking up a lot of resources, but I do think we need to continue with this strategy,« he says.

For now, only one small part of the puzzle remains solved.

Translated by Bibi Christensen.

The original article in Danish is here.